The Human Rights Situation in Tibet

In recent years, the human rights situation in Tibet has garnered significant attention on the international stage. Despite being an autonomous region within China, Tibet remains beset with numerous human rights challenges that prompt global concern and debate. This article delves into various prominent issues affecting this unique region.

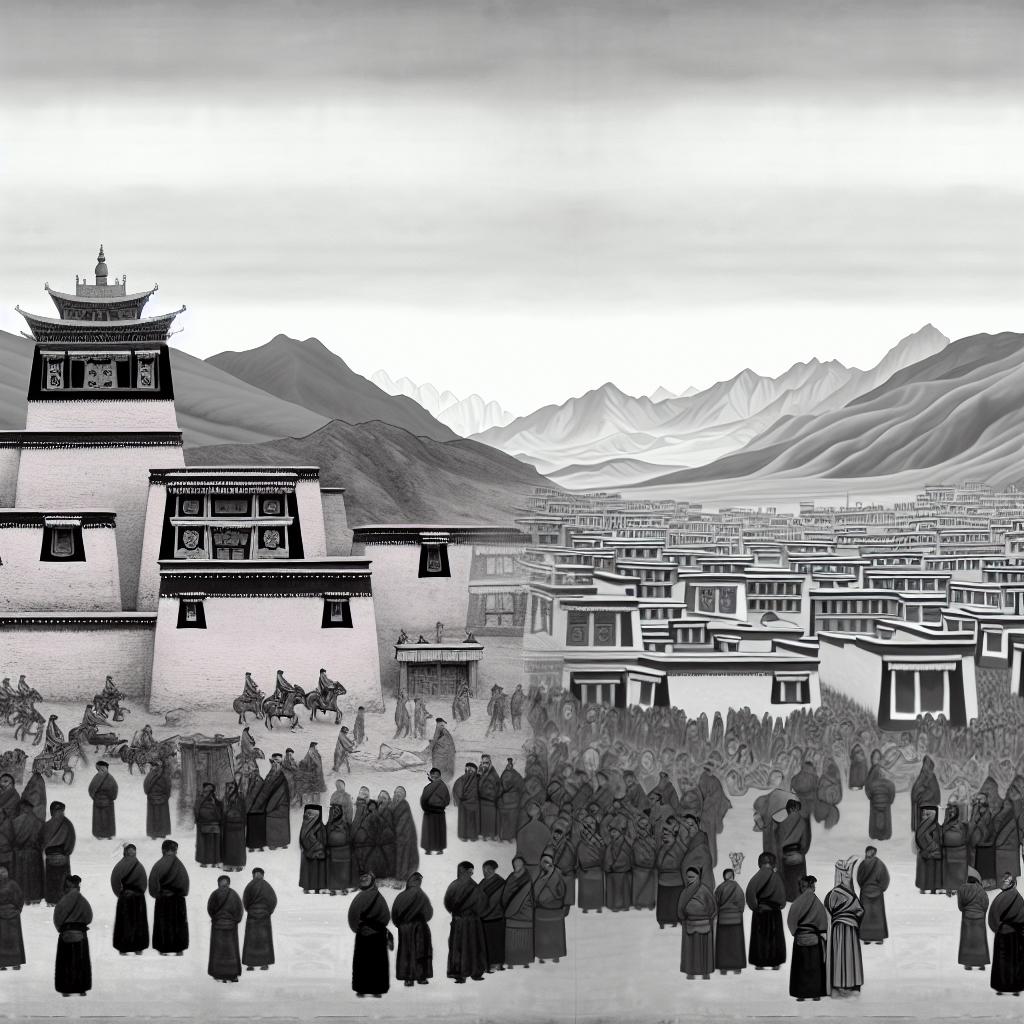

Background on Tibet

Tibet possesses a distinctive cultural, religious, and political heritage, deeply rooted in its predominantly Buddhist traditions. The spiritual leader of Tibetans, the Dalai Lama, holds immense cultural and religious significance. Since the People’s Republic of China established control over Tibet in 1950, there has been an ongoing tug-of-war over the region’s autonomy and the preservation of its cultural identity. These tensions have manifested in numerous ways, impacting the lives of Tibetans profoundly.

Historical Context

Understanding the current human rights situation in Tibet requires acknowledgment of its historical context. The region’s quest for greater autonomy has its roots in several decades of complex interactions between the local Tibetan authorities and the central Chinese government. Efforts to assert autonomy have often been met with resistance, leading to ongoing debates about the degree of autonomy and self-determination the region should possess.

The Role of the Dalai Lama

The Dalai Lama has been a central figure in this discourse, serving not only as a religious leader but also as a symbol of cultural preservation and autonomy for the Tibetan people. His advocacy for non-violence and dialogue underscores the significance of peaceful approaches to conflict resolution. However, his exile and the restrictions on religious freedoms for his followers continue to exacerbate tensions in the region.

Cultural and Religious Rights

Cultural and religious rights form one of the primary concerns within Tibet. Tibetan Buddhism is an integral part of the daily lives and identity of the Tibetan people. Nevertheless, there are reports indicating that Tibetan Buddhists face severe limitations on their religious practices. Surveillance on monasteries has increased, with restrictions imposed on the number of monks and nuns permitted to reside and practice. Such constraints significantly impede the ability of Tibetans to pursue their cultural and religious traditions freely.

Impact on Monastic Life

Monasteries, which serve as critical centers for religious, educational, and cultural activities, are under constant observation. This environment has restricted the religious freedom of both monks and laypeople. Additionally, government intervention in the selection of key religious figures, including the Panchen Lama, further complicates the region’s cultural and religious autonomy.

Freedom of Expression

Another crucial issue in Tibet is the restriction of freedom of expression. The region’s media and journalistic practices are tightly controlled, leaving little room for dissent. Those who attempt to express their views, even in peaceful ways, often face detention or imprisonment. This suppression of expression complicates the maintenance of transparency and accountability, which are vital components of effective governance.

Challenges for Journalists

Journalists working within Tibet operate under challenging conditions, facing significant restrictions that limit the scope of their reporting. As a result, there is a lack of comprehensive and unbiased information reaching both local audiences and the international community. This environment not only restricts the flow of information but also hampers efforts to address human rights concerns through public discourse.

Political Prisoners

The issue of political prisoners in Tibet is persistent, with numerous individuals detained due to their advocacy for human rights or expression of personal opinions. Organizations like Amnesty International have highlighted numerous cases, such as that of Tashi Wangchuk, a prominent advocate for the Tibetan language. These detentions spotlight the ongoing struggle for basic human and political rights in Tibet.

Individual Cases

High-profile cases of imprisonment often garner international attention, serving as rallying points for advocacy groups seeking to shine a light on the human rights situation in Tibet. Efforts to secure the release of these individuals continue, yet significant challenges remain in shifting the policies contributing to these imprisonments.

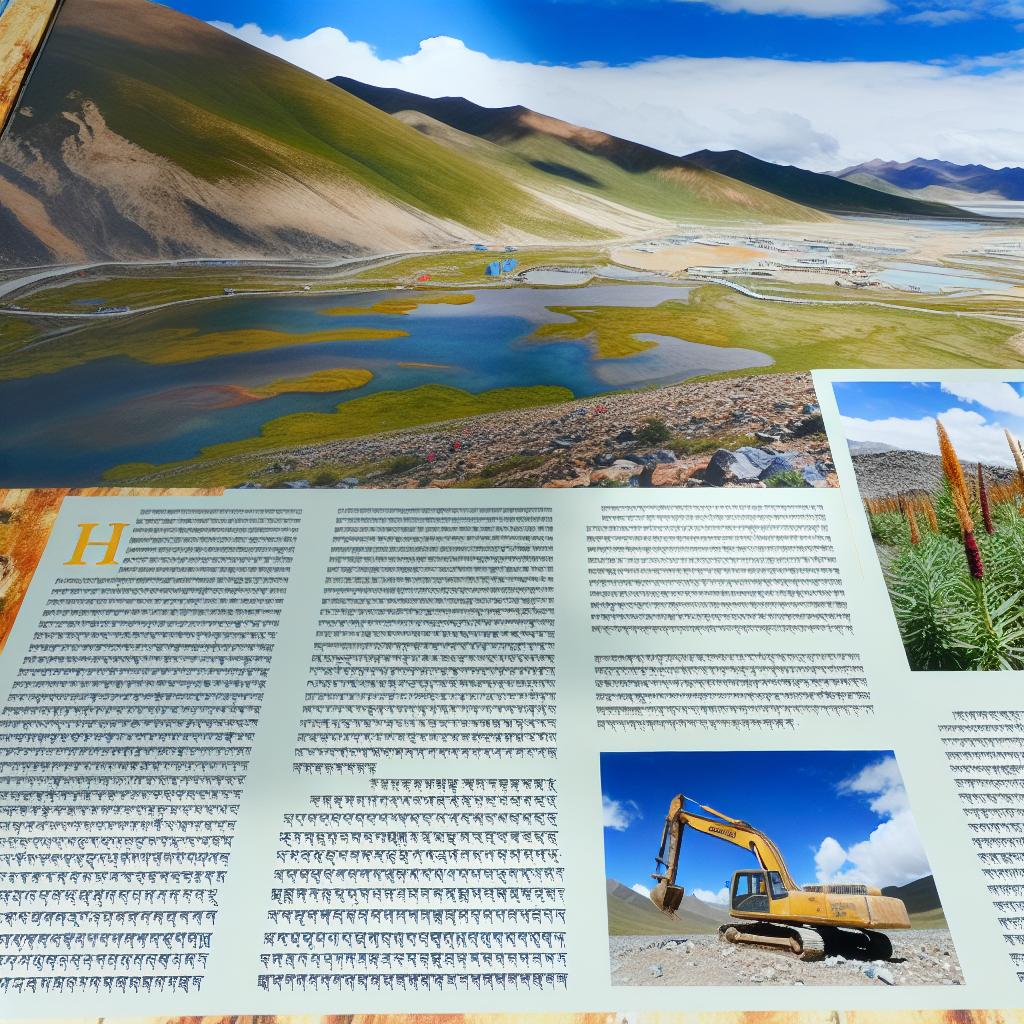

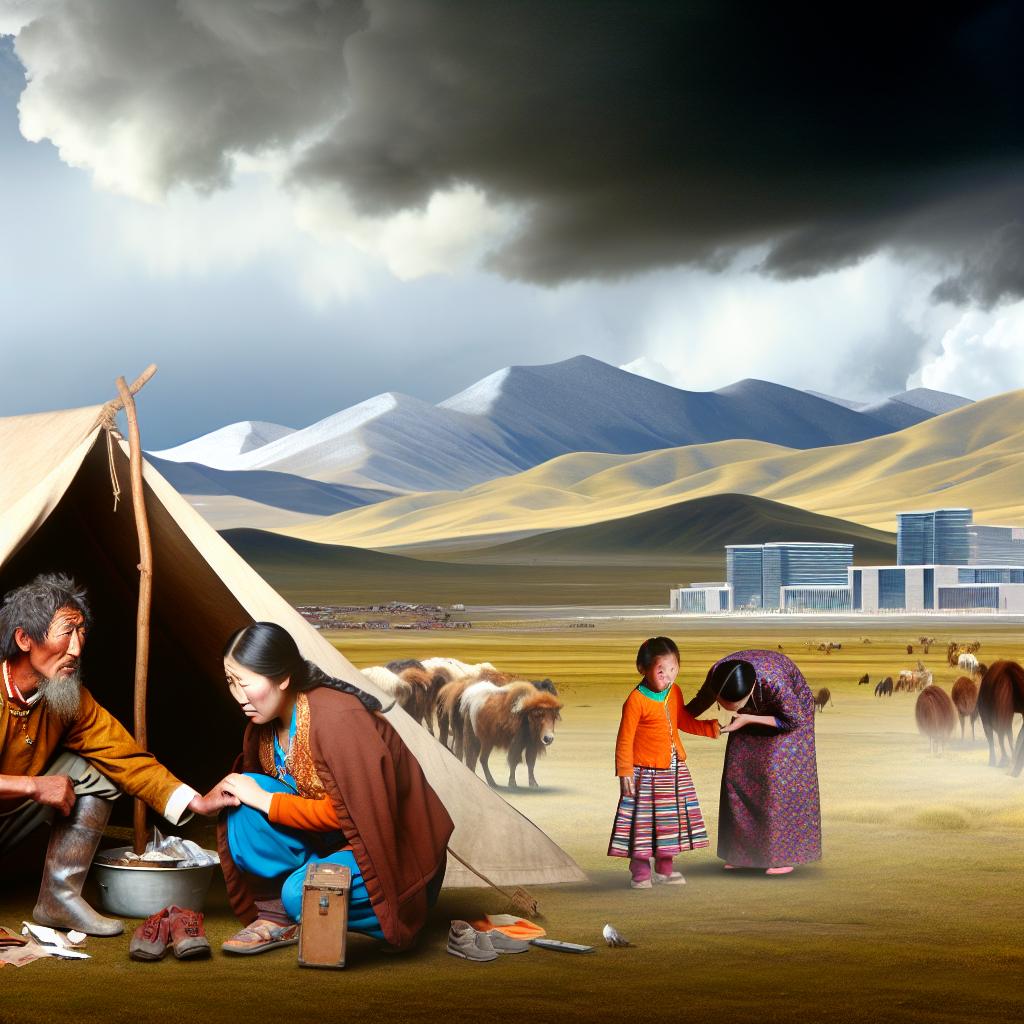

Economic and Social Rights

The economic and social rights of Tibetans are crucial to addressing regional well-being. However, many Tibetans allege that development initiatives are disproportionately benefiting non-Tibetan populations and enterprises. A lack of equitable access to education, employment, and economic opportunities leaves indigenous Tibetans disadvantaged, further deepening social and economic disparities.

Development Projects and Impact

The focus of development projects on benefiting external enterprises often leads to the marginalization of local Tibetan communities. Consequences include limited opportunities for economic advancement for Tibetans and challenges in preserving their social structures and traditional ways of life. Addressing these disparities requires more inclusive development strategies that consider the needs and rights of the indigenous populations.

International Reactions

Concern from the international community regarding Tibet’s human rights situation has been notable, with various governments and organizations urging China to improve conditions in the region. Forums like the United Nations continue to advocate for dialogue and constructive engagement aimed at finding solutions. This international pressure reflects an understanding of the complex issues at play and underscores the need for sustained international monitoring and advocacy.

Diplomatic Efforts

Efforts to enhance human rights in Tibet involve diplomatic channels and international advocacy, which aim to foster discussion and initiate policy changes. The promotion of constructive dialogue between the Chinese government and Tibetan representatives is seen as a crucial avenue for reaching a resolution that respects both national sovereignty and regional autonomy.

For further insights into ongoing efforts to address Tibet’s human rights issues, visiting the Tibet Network website provides access to detailed updates and international advocacy initiatives.

Conclusion

Approaching the human rights situation in Tibet requires an appreciation of the intricate political and cultural dynamics at play. The ongoing dialogue surrounding Tibet’s human rights highlights an urgent need for continued monitoring and advocacy to promote the protection and enhancement of human rights throughout the region. By focusing on equitable development, cultural preservation, and creating channels for expression and dialogue, there is hope for meaningful progress and a future where human rights are fully respected and upheld.